Urban Legend’s Female Villain Feeds the Patriarchy One Kill at a Time

Strong Female Antagonist is a blog dedicated to examining the bad girls of horror, the female monsters, the women we’ve been taught to fear.

I was raised with rigid ideas about what it means to be a “good girl,” most of which revolved around staying in the good graces of men and boys. “Always look pretty (but not slutty). Make him feel important. Don’t make him mad.” As an adult, stepping out of this system of control often feels like donning an “evil” mantle.

I’ve found a lot of comfort in the women of horror, the good and the bad, and I’m fascinated by the female and femme characters who rebel. Are they truly villains or are they victims of a society that sees them as window dressing? Why do some girls go bad, and who gets to decide what “evil “ fundamentally means?

I’m kicking off this series with my favorite female killer, Brenda Bates from the 1998 slasher Urban Legend. For the record, I am not excusing Brenda’s behavior. She is a killer. But she doesn’t exist in a bubble. She is a product of her environment: everything and everyone who came before her. While abhorrent, her crimes, and her motive for committing them, expose the damage internalized patriarchy can cause.

Her Story

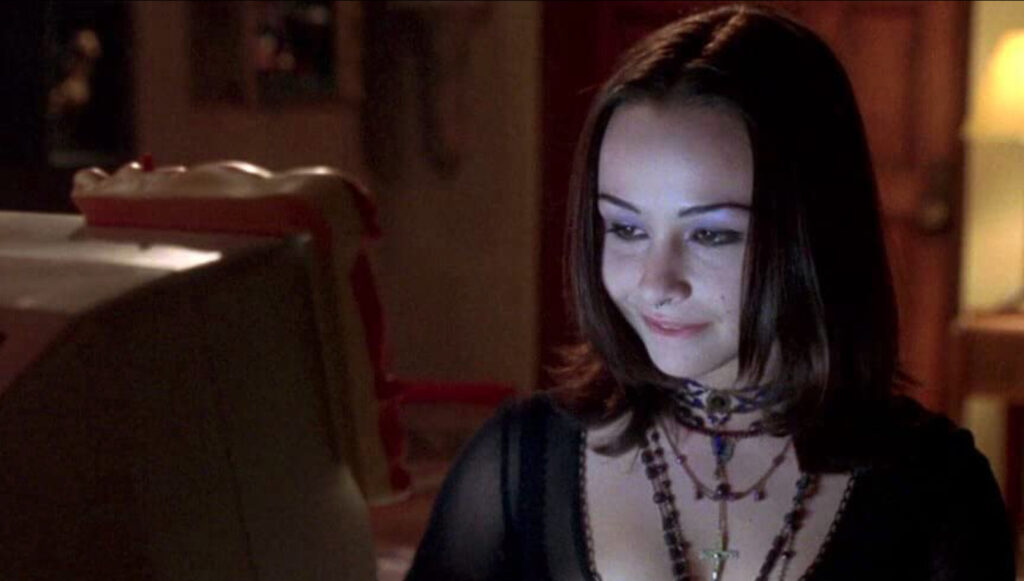

Brenda Bates is a student at Pendleton University and best friend of the film’s final girl, Natalie. She’s enrolled in a course on urban legends when her classmates fall victim to the horrific stories one-by-one. In a fantastically unhinged final monologue, Brenda reveals herself to be the parka-wearing killer and is ultimately defeated by her own urban legend. She’s presumed to be dead, but a final stinger shows her at another candy-colored campus telling the same stories to a new group of potential victims.

Her Weapon

Brenda does not use a signature weapon to kill, but rather the trappings of famous urban legends like axes, ropes, and microwaves. I’ve always been fascinated by these stories passed down as cautionary tales, but which hide a sinister intent. Yes, urban legends reflect societal fears, but they also pass on life lessons for survival often directed at women. “Make sure you check the children. That’s what good babysitters do.” “Don’t go to lover’s lane (code for premarital sex) or a man with a hook will get you.”

Most urban legends exist to subtly tell women how to survive in a world not built to protect them. In order to fully understand how Brenda weaponizes these legends, we need to look at each “UL” she employs to kill and how it impacts the story.

The Killer in the Back Seat

Pendleton student Michelle Mancini drives to a gas station where a creepy attendant tries to coax her into his office. She feels uncomfortable and speeds away, only to find that the real danger is the killer hiding in her back seat. That’s what the attendant was trying to tell her, and because she ran from him, she missed his warning.

The message here is “don’t trust your instincts.” If Michelle had listened to the attendant, ignoring the fact that he made her uncomfortable, she would have survived. But she listened to her gut instead and was felled by the threat secretly lurking in her car. The killer in the back seat tells women to turn off the instincts that warn them of danger and to give that creepy guy another chance. He knows what’s best.

Lover’s Lane

Natalie goes to a secluded area in the woods to “talk” to frat boy Damon. She refuses his advances, and frustrated, he storms out of the car to pee before taking her home. While Natalie waits, Damon is attacked and hanged by the branches of a tree above the car, the rope tied to its axle. With the killer coming, Natalie drives away–and that’s what seals Damon’s fate, as the motion of the car yanks him up and breaks his neck.

Though this legend exists mostly to reinforce gender stereotypes, here it is used to sinister effect. Unlike the protagonist in the urban legend, Natalie is not rescued by the police. Instead, she attempts to save herself by driving away. But this is ultimately what kills Damon as Natalie starting the car sets his death in motion. If she had chosen to keep the car still, putting herself in danger or waiting to be rescued, Damon would have survived. To be clear, Natalie is not responsible for Damon’s death. Brenda sets everything in motion and hands Natalie an impossible choice. But Natalie becomes a victim here too as she is punished with the knowledge that her instincts of self-protection led to Damon’s demise. The lesson becomes “sacrifice yourself to avoid hurting a man.”

The other side of this scene is the danger coming from inside the car. Damon is trying to manipulate Natalie into having sex with him. And her resisting his advances is the first link in the chain that leads to his death. If she had kissed him, he wouldn’t have gotten out of the car and they both would have remained safe. But she chooses to set a physical boundary and is punished for it with the guilt of knowing she caused his death.

You could take this a step backward and say that if Damon had chosen not to try to manipulate Natalie into kissing him, he would be safe. But the film does not explore this and Natalie is presented as the only one with real power. It’s a distillation of rape culture as Damon is just doing what men naturally do (boys will be boys, right?), but it’s Natalie who is punished for her choices.

Brenda gaslights Natalie by stacking the deck against her and ensuring that any action she takes will cause either harm to herself or harm to another person. She can either sacrifice herself or live forever with the guilt of her decision. Women are often punished for setting physical boundaries and manipulative men play the victim. Brenda brings this to life by turning Damon into a victim, killed by Natalie who pushed him away.

Aren’t You Glad You Didn’t Turn On the Lights

Natalie’s roommate is Tosh, a surly “goth girl” into hooking up with strangers she meets online. When her next date turns out to be the killer, she’s attacked and murdered in her dorm room. Natalie arrives in time to save her, but because she had interrupted Tosh’s trysts before, chooses not to turn on the lights, going to sleep while the murder takes place feet from her bed. She wakes up to find Tosh dead with “Aren’t you glad you didn’t turn on the lights” written in blood on the wall.

The message here is basically one of slut-shaming and victim blaming. If Tosh hadn’t been promiscuous, she would have survived because she never would have “asked for it” by inviting the killer to her room. Adding insult to injury, the film moralizes the type of sex Tosh chooses to engage in. If it hadn’t been rough, Natalie wouldn’t have mistaken her attack for another kinky tryst and would have tried to help.

The Unbelievable Scream

At a frat party, Brenda’s friend Sasha learns that the scream heard in the song Love Rollercoaster is the real scream of a woman being murdered. Later that evening, while recording her radio show, Sasha is attacked and her murder is broadcast all over campus. Everyone hears her screams over the airwaves but pays no mind, assuming it’s part of a bit. Natalie is the only one who even attempts to help. This is a clear and devastating lesson that many women know well. “Your pain doesn’t matter and no one will believe you. In fact, your death may even be used as entertainment.”

The Dog in the Microwave

Sasha’s boyfriend Parker has a dog he feeds beer with a funnel as a party trick. In a nod to the story about an old woman who tries to dry her dog in the microwave, this poor pet is similarly killed in grotesque fashion. Brenda then murders Parker by force feeding him drain cleaner with the same type of funnel he used to intoxicate his dog. Parker is punished for failing in his role as caretaker, for stepping into a role traditionally viewed as female, and then not taking it seriously. Nevermind the fact that Brenda actually kills the dog in order to make her point about the value of caregiving. The patriarchy is often more concerned with the message rather than the collateral damage and hypocrisy is par for the course–a gaslighting feature, not a bug.

The Kidney Heist

As her final act of punishment, Brenda plans to perform amateur surgery on Natalie and remove her internal organs. In the legend, a man goes home with a woman he’s met at a bar who then seduces and drugs him. He wakes up in a bathtub full of ice, realizing that his kidney has been removed to be sold on the black market.

The message here is clear: “Women are not to be trusted. They will take a piece of you.” It’s the perfect story to reveal a killer who’s been lurking in front of us the whole time. Brenda uses the patriarchy in her favor, knowing that we are conditioned to see her as a pretty but helpless girl. She might even need us to protect her. But when we let our guard down, she pounces, and we find out she’s been deceiving us from the start.

The Yellow Ribbon

In the final scene, Brenda begins to tell her story to a new group of college students while wearing a blue ribbon around her neck as a choker. It’s a reference to the legend about a man set to marry a woman who always wears a yellow ribbon around her neck. Throughout their courtship she’s refused to take it off or tell him why she wears it. On their wedding night, he finally convinces her to take off the ribbon, and when she does, her head falls off. The yellow ribbon was holding her together and keeping her alive.

Brenda is sustained by her belief in this system of lessons and stories. Her ultimate goal is to turn these stories against the women who fail to heed their warnings, but here the urban legend is a threat to Brenda herself. If she takes the ribbon off and admits that her entire life has been built around a system of control that does not serve her, what will be left? Can she survive without this rigid code?

Her Motive

What arguably makes Brenda such a memorable antagonist is her wild “confession” scene. While holding Natalie captive, Brenda takes excruciating time to explain herself to her victim. Complete with hundreds of candles, a projector, and a visual aid, Brenda lays out the driving motivation behind her trail of terror.

Earlier in the film we learn that Natalie was a passenger in a vehicular homicide case where her friend Michelle (Brenda’s first victim) used the urban legend of the flashing lights to run another driver off the road, accidentally killing him. It turns out that driver was none other than Brenda’s fiancé. The two were going to get married and live happily ever after.

Natalie cost Brenda her prized place in the patriarchy. By securing a husband right after graduation, she’s guaranteed a happy home and a man to provide for her. She’s done what society tells her she’s supposed to do: Find a man to prove that she is valuable. As girls, many of us are raised to believe that the ultimate success is finding a man to love us. That love gives us our value and an acceptable place in our social structure. We’ve been groomed since birth to be attractive, pleasant, and interesting so that we can land the “man of our dreams.” Hopefully we’ll love him.

But it’s not just companionship we’re after. Having a husband, we’re told, will give us safety, someone to provide for us, take care of us, and give us power in a hierarchy based on genetic makeup. When Brenda’s fiancé dies, she loses that status and security. While I don’t deny that Brenda loved him, part of what she’s saying is that Natalie robbed her of the picture perfect life she was probably taught to prize over everything else.

Adding insult to injury is the fact that Natalie also inadvertently foils Brenda’s attempt to find love again with Paul, the blue-eyed student reporter with questionable ethics. Brenda has been into Paul for the entire film, but she just can’t seem to get him to bite. His attraction to Natalie infuriates her, especially because Natalie doesn’t seem to like him much, challenging his actions and making him angry.

Brenda has done everything “right.” She plays by the rules. She flirts. She tries to be fun. But Paul is attracted to the girl who doesn’t conform, who has interests in things other than landing a man. The patriarchy has failed Brenda and she’s angry. Why should the girl who refuses to play the game wind up with the prize? Natalie’s very existence is a threat to Brenda and she must be destroyed.

Her Victims

Urban Legend mostly adheres to the typical slasher formula with Brenda’s victims existing to torture Natalie. But Brenda’s main targets are Natalie and Michelle, the women who caused the death of her fiancé. You would think Brenda would focus most of her rage on Michelle, the person who was driving, but Natalie is her primary target. This serves a practical purpose: Natalie can’t be our final girl if she’s also guilty of vehicular manslaughter. The rules of slashers traditionally require “pure” heroines. But it also feeds the narrative of punishment and the patriarchy itself.

Natalie is punished because it was her car. She didn’t have control, but she bears Brenda’s blame. Every woman knows that story well. “She didn’t do enough to stop it. She should have known better. She was asking for it.” Natalie is just another woman punished for the actions of others because the patriarchy holds her to a higher standard. So what if the actual killer was another woman? Natalie is to blame for failing to stop it.

Her Legacy

On the surface, Urban Legend’s ending of a straight-haired Brenda telling a new story is most likely just a stinger, a fun way to get in one last scare and leave the door open for a sequel. But the reality is that these stories linger on well past their lifetimes. There will always be people telling women what to do, how to act, what to wear, and who to be. And many of them will be fellow women.

The Brendas of the world are dangerous. They exist to simultaneously control us and to legitimize the very system of control they help to prop up. Their power is coming from inside the house. It’s based on their fear of being disposable, cast out for not conforming, and we must be watchful. Because while it’s scary to think that we might fall victim to Brenda, the true danger is that we might become her.