Mommie Dearest and the Dangerous Ideal of Motherhood

Mother’s Day is traditionally viewed as a joyous celebration. Filled with brunches, long-distance phone calls, and flowers, it’s a day to honor the women who gave us life, then sacrificed their own to raise us. But the reality is far more complicated. For many, the second Sunday in May is stressful and triggering. It’s a day when we are forced to confront the memory of a lost child or pregnancy, the death of a parent, or the inability to have children at all. Many more are reminded of the abuses we suffered at our mother’s hands or the abandonment we feel from never having known her at all. Mother’s Day was not designed to celebrate mothers, but instead a feminine ideal, an image of perfection that leaves many of us behind.

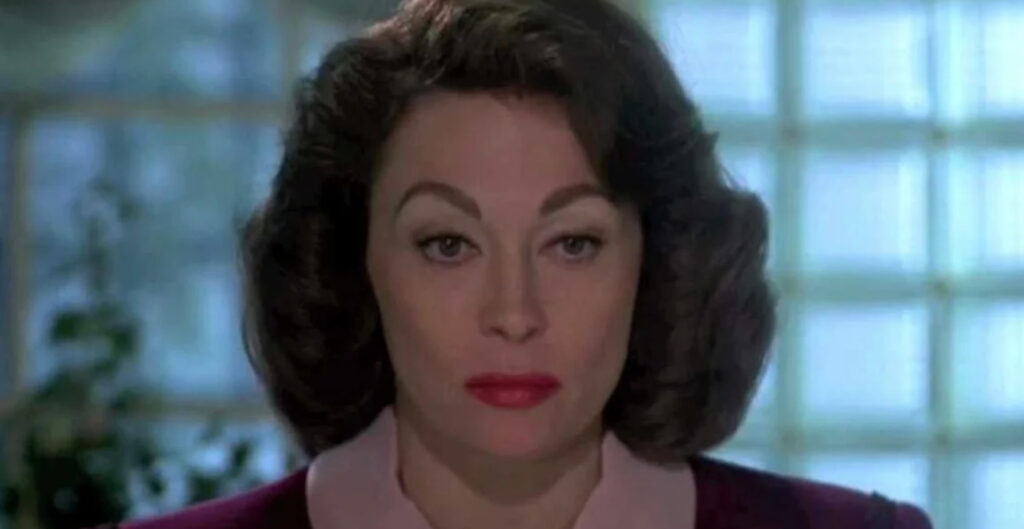

Though cinema is filled with monstrous mothers, few are as iconic as Faye Dunaway’s portrayal of Joan Crawford in Mommie Dearest. Children of the 80s grew up hearing the phrase “no wire coat hangers,” and the image of a cold-cream-wearing banshee screaming at her young daughter was burned into many young brains. I remember watching this movie as a child and finding it funny. The camp is undeniable and it stands as an example of oblivious melodrama. But revisiting the film as an adult was an entirely different experience. Mommie Dearest is a horrific depiction of child abuse dressed up in Hollywood glamour.

Accounts of life inside the Crawford home differ wildly and we will most likely never know where the truth lies. The film’s source material, Mommie Dearest, is a memoir written by Joan’s adopted daughter Christina Crawford after her famous mother passed away. Some say she fabricated these allegations as revenge for being cut out of Joan’s will. Others say the book is a reclamation of power after a lifetime of abuse. There are also unconfirmed reports that Joan herself was a survivor of childhood sexual abuse, adding context to her story while not excusing the actions she’s accused of.

As a survivor of similar abuse, I find this portrayal chillingly authentic and am inclined to believe the events told in the story, however sensationalized they might be. However, for the purposes of this essay, I will be writing about events as they exist in the movie and not speculating on their veracity. The Joan in Frank Perry’s 1981 film is without doubt a villain.

Her Story

The Joan Crawford we meet in the opening sequence is a movie star at the height of fame. No specific titles are mentioned, but the story likely begins in the late 1930s as she’s filming Ice Follies. Though adored by fans, she leads a relatively solitary life, sharing her massive Hollywood mansion with two housekeepers and living apart from her Hollywood lawyer boyfriend. To maintain her benevolent image, Joan is photographed delivering Christmas presents to orphans, and falls in love with the praise she receives for her generosity. She decides that a baby is what’s missing in her life, and while she likely does want a child—or at least believes that as a woman she’s supposed to want one—Joan later admits she partially adopted Christina for extra publicity. Joan wants a perfect child to make her look like a perfect mother, and Christina becomes the ultimate accessory, a testament to Joan’s selflessness and strength.

Her Motive

Joan is a narcissist. The day she adopts infant Christina, she agonizes over her home decor and what dress to wear, wanting everything to be perfect for her big moment. Holding her daughter for the first time, she poses at the top of the stairs, creating a beautiful if awkwardly self-aware tableaux of mother and child. As a movie star, Joan’s career depends on maintaining a flawless image, and she extends this demand for perfection to Christina. But there are two Joans: The vision of maternal bliss she projects to the world and the furious monster beneath. Because perfection is always an illusion, in trying to be a “perfect” mother, she nearly destroys her child.

A veteran actress, Joan knows how to bend the Hollywood system to her will, but she also knows how frustrating the game itself can be for women. She takes this frustration and turns it toward those around her, mostly directing her fury at Christina, who represents a metaphorical challenge to Joan’s youth and vitality. It would be easy to say that Joan’s abuse is born out of resentment at this powerlessness, but many of the most severe beatings she dishes out come after major accomplishments such as booking a coveted role and winning an Academy Award. So instead, the abuse is perhaps a manifestation of deeply held insecurities and fear that these fragile accomplishments will be ripped away at the first sign of deficiency.

A common complaint from those close to Joan is her tendency to “act” in her real life rather than open herself up to authentic interactions. Christina is a part of this performance, but Joan perceives her refusal to play her part as a liability. One misstep by Chistina could reveal to the world that Joan is not perfect and thus not deserving of any of the praise she’s received. When she happens upon Christina playing with makeup and mimicking her famous mother, she becomes enraged and brutally cuts off Christina’s hair. Perhaps this display is too close to the truth that Joan is desperate to hide, a reflection of her own insecurities that must be destroyed.

Her Weapons

Expectations

Unable to empathize with her young daughter, Joan holds Christina to impossibly high standards. She throws an extravagant birthday party, but makes her young daughter donate all but one of her presents. While certainly charitable, Joan likely does it for the publicity and almost seems to relish Christina’s disappointment. A more compassionate way to achieve the same goal would be to guide Christina in donating one used toy for every new one she receives, or simply asking partygoers to donate in Christina’s name. But this would rob Joan of the magnanimous image she craves even over her five-year-old daughter’s feelings.

While lounging by her pool, Joan forces Christina to practice diving over and over again for no discernable reason other than her neverending need for perfection. She races Christina in the pool, giving her a head start, but easily winning and rubbing the loss in her daughter’s face. While this could be spun as teaching resilience, she is forcing her child to participate in a game she has no chance of winning, all in service of her own ego. When Christina protests, she is locked in the pool house.

Coathangers and Floor Cleaner

In the film’s most iconic scene, a likely drunk Joan invades Christina’s closet in the middle of the night and finds a wire coat hanger. She screams at her daughter, throwing armfuls of clothes on the floor and beating her with the offending hanger. Joan sees these fancy clothes as a substitute for the love she is unable to give and calls Christina ungrateful for treating them so carelessly.

Though this scene is arguably the most memorable, often overlooked is its heartbreaking conclusion. Seeing a small spot on the bathroom floor, Joan drags Christina out of bed and berates her for her laziness. She beats her again, this time with an open can of bathroom cleaner, the chemical powder spraying all over the bathroom and her young child. Seemingly spent after this reaction, Joan leaves her sobbing child on the bathroom floor to clean up the wreckage alone.

As a child, Christina would likely have no control over the hangers in her closet and should not be expected to scrub the bathroom floor in the middle of the night. This abuse goes beyond household chores and requires Christina to have maturity and agency simply unavailable to a girl of her age. Joan is not merely punishing her child, but subjugating Christina to her will and counteracting the powerlessness she feels by dominating someone smaller. Joan most likely does not care about the coat hanger or the spot on the floor. They are simply focal points for her fear.

Love

Perhaps Joan’s most insidious weapon is the love she withholds from her child. While playing, Christina and her brother Christopher accidentally disturb Joan’s sleep before an important meeting with the studio. Joan later overhears Christina reflecting the harsh words of punishment she received onto her dolls in an attempt to process the traumatic experience. She returns to her bedroom to find her “babies” missing. Joan coldly uses the same shaming language against the dolls, telling Christina that she should be glad they’re gone so they can’t interrupt Christina’s sleep. She not only punishes Christina for an unflattering representation of her own actions, but reminds her that, like the dolls, she too could be taken away at any moment. This is a threat Joan follows through with, eventually sending Christina to boarding school.

In one of the film’s most upsetting scenes, Joan demands to know why a teenaged Chrisitna won’t give her the love she believes she’s entitled to: The type of love she gets from her fans. She fails to realize that real love is different from idolatry—and this is perhaps the essence of Joan’s conflict with her daughter. She adopted a baby girl thinking she was purchasing a guaranteed source of love and validation without realizing that she had a responsibility to maintain the relationship, too. Infuriated at her inability to command Christina to love her, she attacks, throwing her daughter to the ground and strangling her.

Her Victims

Christina is Joan’s primary victim and the one to absorb most of her rage, though it must be noted that this memoir is written from Christina’s perspective and certainly biased. Christopher is also cut out of Joan’s will, but he doesn’t seem to attract Joan’s rage the way Christina does. As a boy, he likely does not provoke the same feelings of competition. Though Christopher offers support, Christina refuses it, knowing that this assistance would further enrage her mother. She suffers the abuse alone, always coming back with the hope that she will find the right formula to win her mother’s love.

Joan’s live-in housekeeper and confidant Carol Ann is both a victim and an accomplice. Another adult in the house and a witness to Joan’s violent outbursts, she has the power to protect Chirstina, but has been so cowed by Joan that she does nothing. Carol Ann is the one to wake the children up in the middle of the night to help Joan destroy her garden. Carol Ann sits at the table while Joan withholds food in order to force Chrsitina to clean her plate. She watches all of this without stepping in to protect the children.

Of course, Carol Ann is a victim of Joan’s abuse as well. We meet her as she is scolded for improperly cleaning the floor, a precursor to the scene in Christina’s bathroom. While practicing her lines, Joan slaps Carol Ann as part of the scene. She pauses after the slap and we think she’s going to apologize, but she is merely performing the next line in the scene. Joan is so consumed with her own agenda that she doesn’t realize she has hurt Carol Ann. Even her concern is empty.

What’s more, Carol Ann doesn’t seem to have any kind of life outside of Joan’s house. This kind of isolation is a classic tactic of abusers, preventing their victims from gaining any kind of perspective through family and friends. She exists only to serve Joan: To fluff her ego, clean her house, raise her children, and help her abuse them.

Her Legacy

I grew up in a house very similar to Joan’s. My father played the role of Crawford, a domineering and rage-filled narcissist whose unpredictability clouded my days and nights with fear. My own mother played the role of Carol Ann, a silent witness to the abuse and enabler to his rage. Every Mother’s Day, we celebrated my mom for her selflessness and kind demeanor. As a mother myself, I now see this quiet subservience as fear rather than strength, an inability to stand up for herself and for her children.

Joan was a product of her time. She rose from poverty to one of the highest echelons imaginable, and she did it with a mixture of hard work, talent, charm, and luck. I wonder if she ever let herself enjoy it. Though her abuse stemmed from conquering a cruel system that didn’t value her humanity, that does not excuse her actions. She was still responsible for the damage she caused to her child.

This insidious image of idealized motherhood still exists in our culture. Some things have changed, but the expectations for mothers to “have it all” have seemingly skyrocketed. “Lean In” and “Girl Boss” mantras have produced the unhealthy escapism of Mommie Wine Culture. There is no way to be a perfect mother, and our culture’s deification of this harmful ideal is damaging our women, our children, and our society as a whole.

But we are not powerless. As mothers, we have the ability to show our children how to love ourselves simply as we are. I’m currently in therapy to avoid repeating my parents’ mistakes in raising my own children. We can choose to prize humanity over perfection and create a new standard that will ripple down through generations. To paraphrase Christina’s final speech to Joan, if we can throw off the expectations of what motherhood should be, there will be no more pain. We will be free.

Jenn Adams